In Hop Pursuit

Shaun Townsend buries his nose in a handful of flowers. He is the sort of person who stops to smell the roses, but these aren’t roses. These are hops. And Townsend is following his nose in search of hops that will help define a new taste in beer.

The OSU hop breeding program is as bold as the hoppiest IPA. Townsend, OSU’s hop geneticist, is working with Tom Shellhammer, OSU’s brewing chemist, to characterize distinctive traits in hops and breed for those selected traits. Their exploration builds on work by the USDA-Agricultural Research Service breeding program in Corvallis, where some of the industry’s top-selling hops have been developed, including the legendary Cascade hop.

[caption caption="Shaun Townsend, OSU’s hop breeder, performs the sniff-test as the first evaluation of new hop varieties for the brewing industry. (Photo by Lynn Ketchum.)"]  [/caption]

[/caption]

With a big, bitter bite, a sweet grapefruit aroma, and a spicy aftertaste, Cascade inspired upstart brewers to experiment with highly flavored pale ales and IPAs. Since those first craft beers hit the market in the 1980s, brewers have been experimenting with more and varied styles of hoppy beers. Today’s beer aficionados debate the characteristics of hop varieties—Cascade, Willamette, Sterling, Galena, Mt. Hood—the way oenophiles discuss grapes.

This renaissance of hop-forward brewing got a boost in 2010 when Indie Hops founders Roger Worthington and Jim Solberg donated $1 million to start the aroma hop breeding program at Oregon State University. Craft beer has two main types of hops—bittering hops, that give beer its crisp, bitter taste (and kill bacteria); and aroma hops, that give beer complex, varied aromas. Today, about 75 percent of hops produced in the U.S. comes from the Yakima Valley in central Washington, a hot, arid climate famous for its bittering hops. Oregon’s Willamette Valley, with its milder, moister climate, is a perfect place to grow aroma hops.

The focus of hop breeding is the unpollinated female flower of the climbing plant Humulus lupulus, a member of the family Cannabaceae (which also includes, yes, cannabis). The pinecone-shaped, strawberry-sized flower is rich with fragrant oils that give beer its characteristic crisp taste as well as a huge range of aromas. Rubbing the cones in your hands is the time-honored way to release the sticky oils and subtle aromas.

But these aromatic oils are volatile. Their floral and citrus fragrances boil away within minutes when added to malted grain and water and heated into a malty liquid called wort. So craft brewers are adding hops—lots of hops—after the wort has cooled and nearly finished fermenting. The oils remain to give the beer a floral essence and an intense flavor.

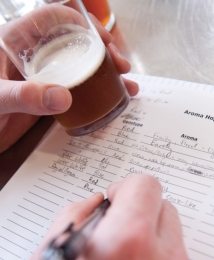

[caption caption="Hop variety trials include tests among trained tasters who evaluate details of aroma and flavors in the resulting beers. (Photo by Lynn Ketchum.)"]  [/caption]

[/caption]

Using an array of analytical tools, including gas chromatographs to test hop oil, brewing scientists are exploring hundreds of aroma compounds and how each affects flavor and aroma. But out in the hop yard, Townsend’s first priority is good agronomics. “Our goal is to produce a new variety that will create exciting flavors for brewers,” he says. “But if a new hop can’t produce a good yield with good resistance to disease and pests, it’s unlikely to make it into full production regardless of its aroma quality."

To that end, Townsend has evaluatedmore than 2,000 hop genotypes throughthe Indie Hops partnership. The first ofthese to be commercialized is Strata, asuperior Humulus with a hint of the familyCannabaceae. For years as an experimentalcross, it was referred to as X-331, a codename worthy of international intrigue.

“We chose to advance X-331 from the OSU research plots to the commercial farm plots because she was vigorous, highly disease resistant, and powerfully pungent (strong odors can repel insects, a few mammals, and thwart certain fungi),”Roger Worthington told industry newsletter New School Beer. But it was the aromathat sold him and convinced panels ofexperts. When they did the rub-and-snifftest on X-331’s oily cones, they described aromas such as dank and earthy. When they sipped IPA made from X-331, they described multiple layers of passion fruit, grapefruit, and mango with a whiff of marijuana smoke. Strata was born.

And hop breeding continues. “Craftbrewers seek variety,” Townsend says. “A hop such as Strata offers them new aromas and flavors with each style of beer.” Unlike the large-scale brewers of fizzy yellow lager, this generation of craft brewers aims for distinction over consistency. And West Coast craft brewers have the added distinction of a new found sense of terroir and locally grown hops to infuse their beers with bright, new aromas.