The Nutty Professors

Tap, tap-crack; tap, tap-crack; tap, tap-crack.

Is it the sound of a gourmet enjoying a crab leg dinner? Or maybe it's a sculptor putting the finishing touches on a work of art. No, it's the sound of crack-out testing. To a hazelnut breeder, that means cracking open individual nuts by hand to evaluate the quality of the kernels inside. It's been going on for years in the

Oregon State University hazelnut breeding program, which gradually has grown into the largest such research project in the world.

Researchers have been cracking away in search of ever better hazelnuts since the late 1960s when the OSU hazelnut breeding program began. Every year they harvest a new crop of hazelnuts from experimental selections growing at field research facilities near Corvallis. The nuts are bagged, dried and delivered to a field lab, fondly called "the nut house" by those who toil there. The researchers take samples from the bags and, using little hammers, crack each nut. It's time-consuming, dull and repetitive work, but it's the only way to decide whether the tree that produced the nut should be kept or cut into firewood.

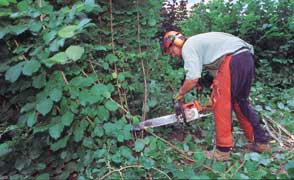

And three decades of research has produced a lot of firewood. Technicians plant thousands of new experimental hazelnut trees annually at the OSU Vegetable Crops Research Farm near Corvallis. Most don't make it.

"We're looking for the top 0.5 percent of what we develop in the program," said Shawn Mehlenbacher, OSU hazelnut breeder and program director. "When our evaluations of nut quality, and many other characteristics, show that a tree is failing to produce, we get the chainsaw and cut it."

|

|

Left to right: Anita Azarenko, a horticulture professor who is testing experimental filbert trees; OSU filbert breeder Shawn Mehlenbacher; USDA research pathologist Jack Pinkerton; and Lane County extension agent Ross Penhallegon. Photo: Bob Rost |

Heading the list of the many characteristics Mehlenbacher looks for in his experimental hazelnut varieties is immunity to eastern filbert blight (EFB), a dreaded disease which has the potential to decimate the state's multimillion dollar hazelnut industry.

Eastern filbert blight was known in the Pacific Northwest in the 1970s, but was not discovered in the Willamette Valley until 1986, just a month after Shawn Mehlenbacher arrived at OSU to take over leadership of the OSU hazelnut breeding program from his predecessor, Maxine Thompson, who retired. The disease appeared first in a hazelnut orchard near Damascus at the northern end of the Willamette Valley. It has been slowly creeping south ever since.

Unfortunately for Oregon growers, three of the top hazelnut varieties in Oregon orchards, Ennis, Daviana and Casina, are extremely susceptible to EFB. The most frequently planted variety, Barcelona, is not as ideal a host for infection as the other three, but is still susceptible to the disease. The blight will eventually kill any tree it infects.

|

|

OSU senior research assistant Dave Smith cleans hazelnuts from an experimental tree. Photo: Bob Rost |

Following the discovery of EFB in Oregon, developing resistant and immune varieties became the paramount goal of the program. In the early 1970s Ron Cameron, a now-retired OSU plant pathologist, and Maxine Thompson discovered full immunity to the disease in a hazelnut variety named Gasaway.

This variety is very poor for hazelnut production, but in 1976 Thompson began using it as a parent in cross-breeding experiments. In the late 1980s, Mehlenbacher summarized the results of Thompson's work and continued breeding research to combine EFB immunity from Gasaway with many other desirable hazelnut characteristics in new varieties.

"This would be easy if EFB immunity was the only goal," said Mehlenbacher. "However, growers are looking for many other traits in a new variety."

For example, growers want varieties that:

- Yield generous quantities of nice round nuts inside thin shells that are easy to crack.

- Bear nuts at an early age.

- Produce nuts that separate easily from their husks.

- Produce nuts that fall from the trees before the first of October, when fall rains usually begin in western Oregon.

- Yield nuts with a low percentage of moldy kernels and a low percentage of blank, or empty, shells.

- Are resistant to the big bud mite, a hazelnut pest.

Developing and testing a new hazelnut variety usually takes 16 to 17 years-8 to 9 years as a seedling and 8 years in replicated tests. During the initial 8- to 9-year development phase, researchers cross-breed desirable parent varieties with experimental groups of trees.

|

|

Research assistant Kais Ebrahem introduces pollen from a promising filbert tree into the buds of another promising tree. This breeding process is called cross pollination. The plastic sheeting prevents wind-blown pollen from other nearby trees from beating him to the job. Photo: Bob Rost |

They succeed when an experimental tree consistently expresses good nut-producing characteristics. Experimental varieties that complete the first stage of the breeding program then graduate to an 8-year period of field testing when researchers evaluate the trees' stability under normal growing conditions. So far, the program has produced the moderately EFB-resistant varieties Willamette and Lewis. Another EFB-resistant variety, Clark, is due for release next year. Mehlenbacher hopes to release a variety with immunity to EFB in the year 2004.

It all takes time, and a fantastic amount of hard work. Consider:

During the last 12 years, since he came to OSU, Mehlenbacher, his senior research assistant, Dave Smith, and their research team have planted nearly 50,000 trees, cracked out millions of hazelnuts, collected hundreds of vials of pollen (for cross-pollination work) and spent countless hours in greenhouses and laboratories growing trees and collecting leaf tissue samples.

There's never a time when there isn't something to do. They harvest nuts from experimental varieties and plant new generations of experimental trees in the fall; cross-pollinate varieties and conduct crack-out testing in the winter; test

new varieties for EFB resistance in the spring; and in the summer, prepare a new generation of experimental trees in the greenhouse for field planting Mehlenbacher has streamlined this busy annual cycle of activity somewhat by incorporating some of the new techniques of gene technology into the hazelnut

breeding program.

|

|

The hazelnut breeding effort dates back to the 1960s. Horticulture professor and breeder Shawn Mehlenbacher inherited leadership of the program when he came to OSU 12 years ago. Photo: Bob Rost |

"There is no substitute for the years of field trials required to test new varieties, but the use of gene technology allows us to save some time and space in the process," said Mehlenbacher.

"Under the system used in the hazelnut breeding program, we move 5,000 seedling trees out of the greenhouse and into the field every year," he added. "And in the past, we've had to grow trees three to four years before evaluating them for signs of EFB resistance or susceptibility."

However, by using scientific processes called the polymerase chain reaction and gel electrophoresis, researchers are able to test seedlings for the presence of a DNA marker for immunity to eastern filbert blight by analyzing leaf tissue samples, which are available as soon as a tree sprouts its first leaf.

Since tree seedlings show leafy growth fairly soon after planting in the greenhouse, the ability to examine them for EFB at that early stage of development saves hundreds of hours that might be invested in moving and transplanting trees, and acres of space in the field needed to accommodate transplanted trees.

"We can use the savings in time and space to increase the numbers of crosses that we make and analyze each year," said Mehlenbacher.

Hazelnut grower Bruce Chapin is enthusiastic about the breeding program, but he emphasizes the immediate need for control measures.

Chapin, who farms near Keizer just north of Salem, enjoys the dubious honor of owning the southernmost hazelnut orchard in the Willamette Valley where EFB has been found.

|

|

Patrick Hund, a temporary worker at OSU's Vegetable Crops Research Farm, cuts experimental trees judged not to have the right qualities, including, of course, resistance to eastern filbert blight. Photo: Bob Rost |

"Development of new varieties is important, but it doesn't help growers who are trying to control the disease now," Chapin said. "The pruning techniques and fungicide sprays we have are effective to a certain point, but if we could find one more control measure it would really help us hold the line against EFB."

Jay Pscheidt, a plant pathologist with the OSU Extension Service, has been hard at work for several years trying to develop additional EFB controls. Pscheidt arrived at OSU in 1988, just about the time that the university's EFB research effort began expanding.

"A team of scientists from the OSU Department of Horticulture, the OSU Department of Botany and Plant Pathology and the USDA Agricultural Research Service have been working on EFB for more than a decade," said Pscheidt. "We've learned a lot about the disease which has helped us improve the effectiveness of pruning techniques and timing of fungicide sprays for control of EFB."

|

|

China Lundy, a graduate student in OSU's horticulture department, inoculates experimental trees with eastern filbert blight spores. In six months, leaf tissue samples will be analyzed. Photo: Bob Rost |

Pscheidt and others at OSU working on EFB are looking at the possibility of biological controls.

"We know that pustules, or concentrations of blight fungus on infected trees, emit spores throughout the winter, but new infections only occur during spring when spring growth appears," said Pscheidt. "That gives us all winter to try eliminating spores through some type of biological means. We know that slugs, some insects, some types of fungi and some bacteria will eat EFB spores," Pscheidt explained. "But in order to achieve significant control any biological measure would have to be 99 percent effective and we haven't figured out how to reach that level, yet," he said.

While Pscheidt works on finding new EFB controls, OSU Extension Service colleagues in the northern and southern Willamette Valley work directly with growers to stem the tide of EFB.

In Yamhill County, extension agent Jeff Olsen is working on an economic analysis of the costs of hazelnut production, the costs of establishing new orchards, and the costs of EFB control. Information from this analysis will help growers make better decisions about how to contend with EFB as new resistant

and immune hazelnut varieties become available, according to Olsen.

In the south Willamette Valley, which so far is EFB free, Ross Penhallegon, a regional extension agent based in Lane County, has a different role in OSU's war against the disease.

"We want to keep EFB out of this area," said Penhallegon, "and that means keeping a sharp eye out for hazelnut trees that may be infected."

He promptly checks out all reports of possibly infected trees. When an infected tree is found, the Oregon Hazelnut Commission offers a $100 reward to have it destroyed.

|

|

|

|

Each fall thousands of trees started in a greenhouse are planted outside. Few make it past the program's early evaluation "cuts.". Photo: Bob Rost |

Commercial harvest at Wayne Chambers' orchard north of Albany. This sweeper pushes fallen nuts to the middle of the row. Photo: Bob Rost |

"We're lucky to have extension agents like Ross looking out for us," said Rodney Chase, a Springfield-area hazelnut grower. Still, Chase admits that it's just a matter of time until the disease spreads to the southern half of the valley. He is getting ready by trying some of the new OSU hazelnut varieties.

"I've got two acres of the new Lewis variety and I've planted some of the other experimental varieties from OSU that haven't been released yet," Chase said. "It's good to get some of these new trees out in the orchard for a few years to see how they'll do."

By the middle of the next decade, Chase and Oregon's other hazelnut growers may have the EFB-proof hazelnut variety they're hoping for. In the meantime, those bags of hazelnuts keep piling up at OSU's nut house. And whenever members of the hazelnut research team find a little time on their hands, out come the little hammers: tap, tap-crack; tap, tap-crack; tap, tap-crack.